Last week I took a look at four superhero characters – Batman, Captain Marvel, Iron Man, and Starfire – and what made them decide to put on their costumes and fight the good fight. If you haven’t read that one yet, I’d suggest checking it out before you read this week’s installment. It will give you some context for where I’m starting with this article.

My last article noted that a lot of popular superhero characters, including all four that we took an in-depth look at, had incredibly traumatic experiences that directly lead to them becoming heroes. According to the World English Dictionary, a superhero is “any of various comic-strip characters with superhuman abilities or magical powers, wearing a distinctive costume, and fighting against evil.” We can break it down even more: a superhero is someone who has skills that Joe Smith on the street doesn’t have, and who disguises his or her identity in order to fight crime with the help of those skills. Nowhere in that definition does it say that a superhero has to have a tragic back-story, but it happens more often than not. Given a little thought, the reason becomes clear.

If you’ve been keeping up with Comic POW!, then you’ve seen Eric’s recent article about the prevalence of violence in comic stories. It’s difficult to think of a story that doesn’t focus on violence in some way; even when we narrow the focus to origins rather than story arcs in general, we find the same trend holding true. It’s easy to fall back on violence as the main form of conflict in any given story, which is part of why it’s so common.

Another reason it’s so popular is because consumers tend to use fiction as a means of escapism and fantasy. That’s why there aren’t a lot of stories about accountants balancing books (without first altering them) or mechanics fixing cars (without doing something shady to them) or other regular people doing regular things. We want to experience things that are outside of the norm for us, so we need the stories that we seek out to have something that we’re unlikely to experience in our day-to-day lives. Instead of conflicts that we might experience (like someone drinking the last of the milk and not putting it on the shopping list or someone taking the parking spot we were planning on using), we end up with villains like Darkseid or Loki trying to destroy the world as we know it for reasons that are often beyond our control. They’re outside of our realm of experience, which makes them interesting; at the same time, these stories have elements to them that make it impossible for them to exist in the real world, which makes it safe to be interested in them.

Violence is a common form of conflict, but it doesn’t have to be the only one. As I mentioned last week, there are several prominent superheroes who began their careers without that violent inciting incident, and they are no less heroic for it. Barry Allen and Wally West owe their super-speed to science rather than tragedy; all four original members of the Fantastic Four were exposed to radiation while in space. Nobody would try to deny that the Flash or the Fantastic Four have had tremendous impacts on their respective universes.

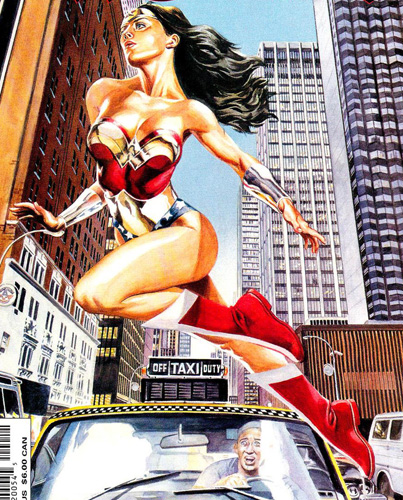

Wonder Woman is perhaps the most striking example when thinking about nonviolent origin stories. In fact, Wonder Woman was specifically created to counter the violent origins that had already become common by the early 1940s. Psychologist William Moulton Marston realized that there were no strong female role models in comics, and together with publisher Maxwell Charles Gaines, sought to change that. Marston famously said:

“Not even girls want to be girls so long as our feminine archetype lacks force, strength, and power. Not wanting to be girls, they don’t want to be tender, submissive, peace-loving as good women are. Women’s strong qualities have become despised because of their weakness. The obvious remedy is to create a feminine character with all the strength of Superman plus all the allure of a good and beautiful woman.”

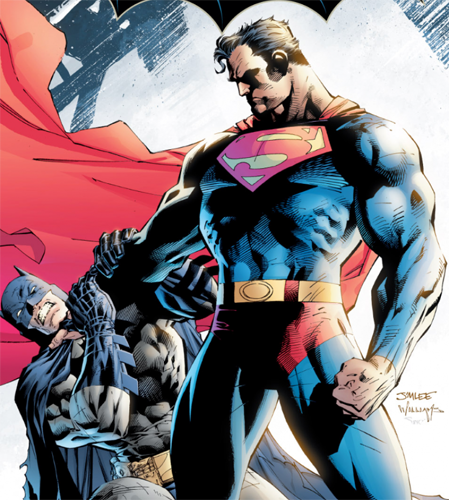

Marston’s response to this idea was to create Wonder Woman, who did indeed have powers that were close to Superman’s, with the addition of her bullet-blocking bracelets, her Lasso of Truth, and her mission of peace and diplomacy. Though she joins the Justice League and continues her solo adventures (neither of which are always or even often peaceful endeavors), Wonder Woman remains true to her roots. Her origin isn’t full of trauma and violence, and she isn’t any weaker for not having that experience.

Now, I’m not trying to say that superhero characters without these violent origins are any better than their counterparts. Some of my favorite superheroes do have a tragic past, while others don’t. I think it creates a strange precedent that so many superheroes – characters that we’re meant to admire and, in some cases, want to emulate – have a past that most people would agree is something we’d all rather avoid. We can want to be like Batman, but you can’t be Batman without having your parents killed in front of you at a young age. We might want to emulate Iron Man, but without the experience that he went through while captured, we can’t get into his mind, either.

The flip side of this is kind of disturbing as well. We’re shown a lot of characters who have these traumatic experiences in their past, and in every case I can think of, the victim in that experience either becomes a hero or becomes a villain. Yes, that sort of thing can change a person in a lot of significant ways, but you never see someone actually recover from a traumatic experience in a comic book. If the trauma happens to a main character, it either strengthens their resolve, or it makes them crack. If it happens to someone who isn’t in the focus, most of the time they get written out of the story entirely. I don’t need my comics to be completely realistic – like I said before, the fact that comics are so outrageous is a big part of their charm – but at the same time, having a storyline where something terrible happens and the character in question actually talks to someone about it or, Heaven forbid, gets therapy and recovers would be a nice change of pace every now and again.

So if it isn’t tragedy that makes someone a superhero, what is it? I think it’s simpler than a lot of people make it out to be: a superhero is someone who wants to help other people, and has the ability and drive to make that happen. The tragic back-story might be what opens their eyes to the need for their specific skill set, as with Iron Man, or they might be doing it as a way to rise above what happened to them in their past, like Starfire did. On the other hand, they might be more like Superman, who helps people because he’s a good person at his core and he knows that he can make a difference. The thing that ties these people together isn’t any one turning point that they all experienced – it’s a trait that they share, and it’s that trait that we admire in them. They want to do good in the world, and no matter what their reasons are for wanting to do so, they all give us something to which we can aspire.

Fantastic Four, Vol. 1 (Marvel Masterworks). Written by Stan Lee; art by Jack Kirby. Published 2003; collects Fantastic Four #1-10 Find it on Amazon or buy it from comixology.

Flash: Terminal Velocity. Written by Mark Waid; art by Oscar Jimenez, Salvador Larroca, and Tom McCraw. Published 1995; collects The Flash Vol. 2 #0, #95-100. Find it on Amazon or buy it from comixology.

Wonder Woman, Vol. 1: Gods and Mortals. Written by George Perez and Greg Potter; art by George Perez. Published 2004; collects Wonder Woman Vol. 2 #1-7. Find it on Amazon or buy it from comixology.

Comments? Questions? Leave a reply! I’ll be happy to talk comics with you.

Great Conclusion to your 2-parter. As to your definition of a Super Hero: I think it’d be neat, if you were interested, to explore Supers who hide their identity vs those who don’t and what effects, if any, that has. For example, in Civil War after Iron Man convinced Spider-Man to reveal his identity, a bunch of criminals went after Aunt May and MJ. In the Batman Books we have yet to see any real consequences to Bruce revealing that he sponsors Batman. Sure, it’s not the same as showing his identity, but a lot of people thought it would lead to problems for Wayne Enterprises. There was mention of it early on in The Dark Knight, but nothing recently. Perhaps a part of that was derailed by the New 52 and how we’ve had to rehash a lot of older things (see Zero Year), but I guess we’ll see.

That would be a really interesting idea! I’ll give it some thought 🙂 There’s definitely lot to explore between those who reveal their identities and those who choose not to.